America’s bomber force is now in crisis. In the Air Force’s fiscal 2021 budget request, one-third of the B-1 fleet is set for retirement, B-2 survivability modernization is canceled and the new B-21 is at least a decade away from contributing significantly to the bomber force. The venerable B-52 requires new engines and other upgrades to be effective. The number of bombers are at their lowest ever, but demand for bombers increases every year, particularly in the vast and most-stressed region of the Indo-Pacific. Bombers are the preferred weapon system there because of their long range and huge payload capacity.

At the end of the Cold War in 1989 and just prior to the Gulf War in 1990, America had over 400 bombers. After these proposed cuts, there will be only 140.

This decline is curious in light of recent Air Force declarations and testimony before Congress. In the document “The Air Force We Need,” Air Force leaders insisted last fall they need five more bomber squadrons — about 65 more bombers. Just last month, the Air Force chief of staff testified that the need is for “200 bombers, of which 145 would be B-21s.” These numbers have been validated by think tanks such as MITRE Corp., the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, Rand, and the Mitchell Institute.

In today’s global threat picture, bombers become the coin of the realm. Bombers have dual strategic roles. They provide flexible deterrence with their nuclear capability, forcing adversaries to think twice before starting an attack. Bombers also carry the brunt of conventional operations.

In our wars in the Middle East, the B-1s, B-2s and B-52s have all played central roles attacking fixed targets and in close-air support of ground troops. Their long range and on-station times, combined with huge weapons loads, make them the weapon of choice for combatant commanders in both the Middle East and Pacific regions.

RELATED

A single B-2 can carry and launch 80 precision-guided weapons, each assigned a different target, and can penetrate contested airspace. The B-1s and the B-52s have similar direct-attack capabilities plus the ability to carry and launch cruise missiles from standoff ranges. No other weapon system, in the air or on the sea, can come close to this massive firepower.

The need for more bombers is increasing. Whether facing nonstate actors like ISIS, mid-tier threats like North Korea and Iran, or peer threats such as China and Russia, the ability to strike targets quickly and in large numbers is crucial. This flexibility was vividly demonstrated in the first three months of Operation Enduring Freedom after 9/11. Bombers flew 20 percent of all sorties, but dropped 76 percent of the munition tonnage. Despite those who thought bombers were only useful in long-range nuclear or strategic missions, the reality is that a wide variety of combat missions are simply impossible to execute without bombers.

But bombers and their crews are worn thin. The Air Force bought 100 B-1s in the 1980s. When demand for them surged post 9/11, the Air Force retired 30 B-1s to free up funding to sustain the remaining force. This, combined with earlier divestitures, saw the Air Force fly 61 B-1s relentlessly for nearly 20 years. The fleet was in such bad shape in 2019 that mission-capability rates were less than 10 percent. The Air Force’s request to retire a further 17 B-1s to boost the health of the remaining fleet looks like a repeat of the last B-1 retirements.

Among the 140 bombers that remain, only the 20 stealthy B-2s have the ability to penetrate modern air defenses to strike critical targets — a priority of the National Defense Strategy. Yet the FY21 budget request cancels the B-2’s Defensive Management System Modernization program and puts our only operational stealth bomber on a path to early retirement. Given the unmet demand for penetrating platforms and the time it will take for the B-21 to be delivered in numbers, halting modernization of the 20 stealth bombers we have today is risky.

Finally, the 78 B-52Hs are planned to be re-engined in the years ahead. New, fuel-efficient and more reliable engines should increase their life and capability. The ultimate cost of this modification is not known. One of the unknowns is the extent of corrosive structural and wiring problems that will inevitably emerge when each B-52 is unbuttoned.

Discovery of such problems is not new. When the Air Force upgraded its C-5M fleet with new engines, the Air Force had to retire the older C-5A fleet to pay for unknown repairs. Even if the B-52 re-engining goes smoothly, a significant portion of the force will be unavailable as each moves through the depot for modifications.

Last year Congress increased funding for the F-35 fighter and added funds for unrequested F-15EX procurement. Now is the time for Congress to restore funding for existing bombers to avoid this shortfall in a most vital component of our nation’s defense.

The Air Force entered the new decade with the smallest bomber force in its history, and the FY21 budget request erodes it further. There comes a point where doing more with less does not work, especially with B-21s not available in numbers for several years. It is time to recognize the gravity of the situation and build up the nation’s bomber force. A good “plan B” does not exist without bombers.

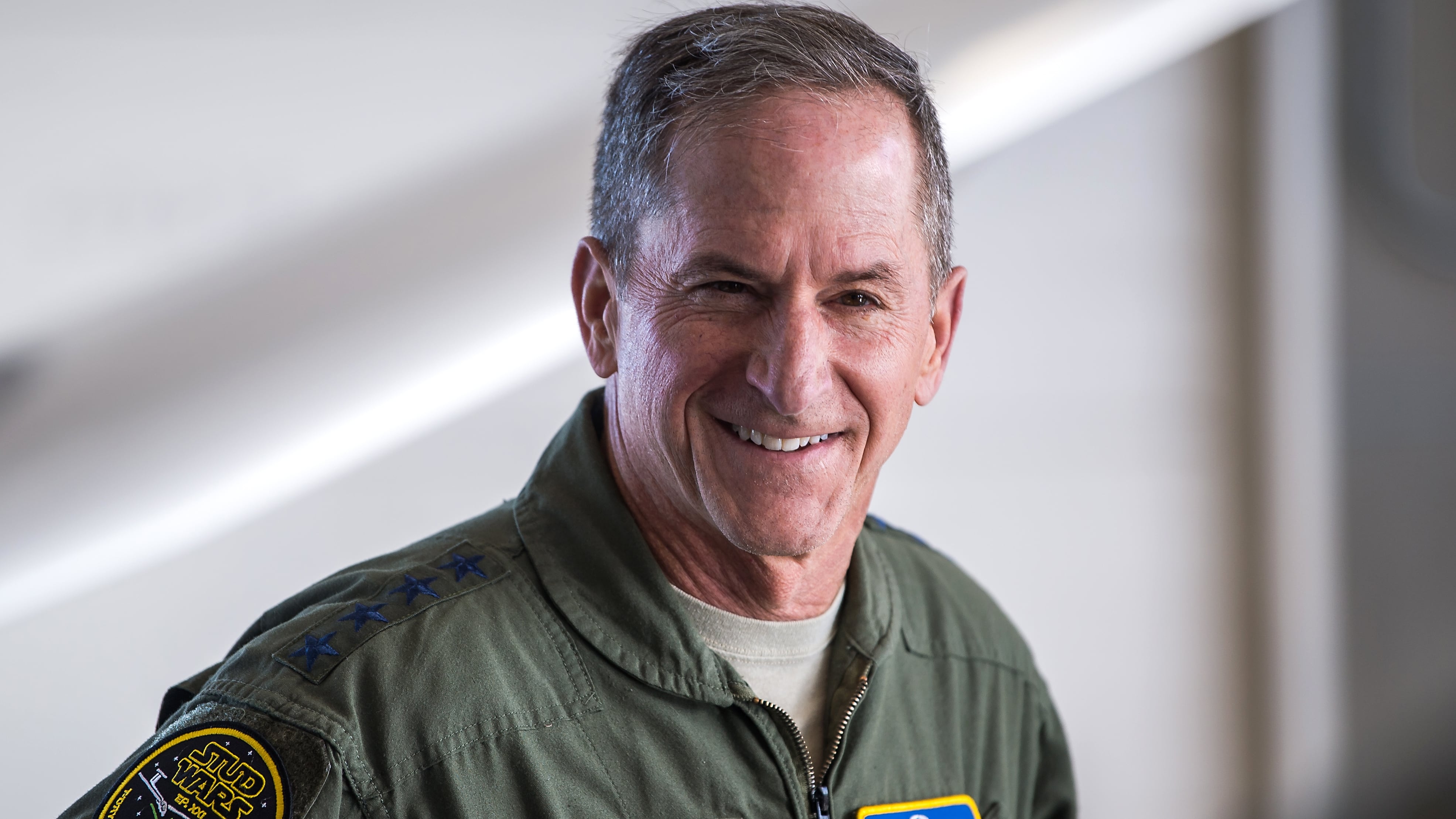

Gen. John Michael Loh is a former U.S. Air Force vice chief of staff and had served as the commander of Air Combat Command.