U.S. economic and military competition with China is the defining condition of this decade and, likely, of decades to follow. The outcome of today’s competition with China rests on who will assume technology leadership for advanced and emerging technologies.

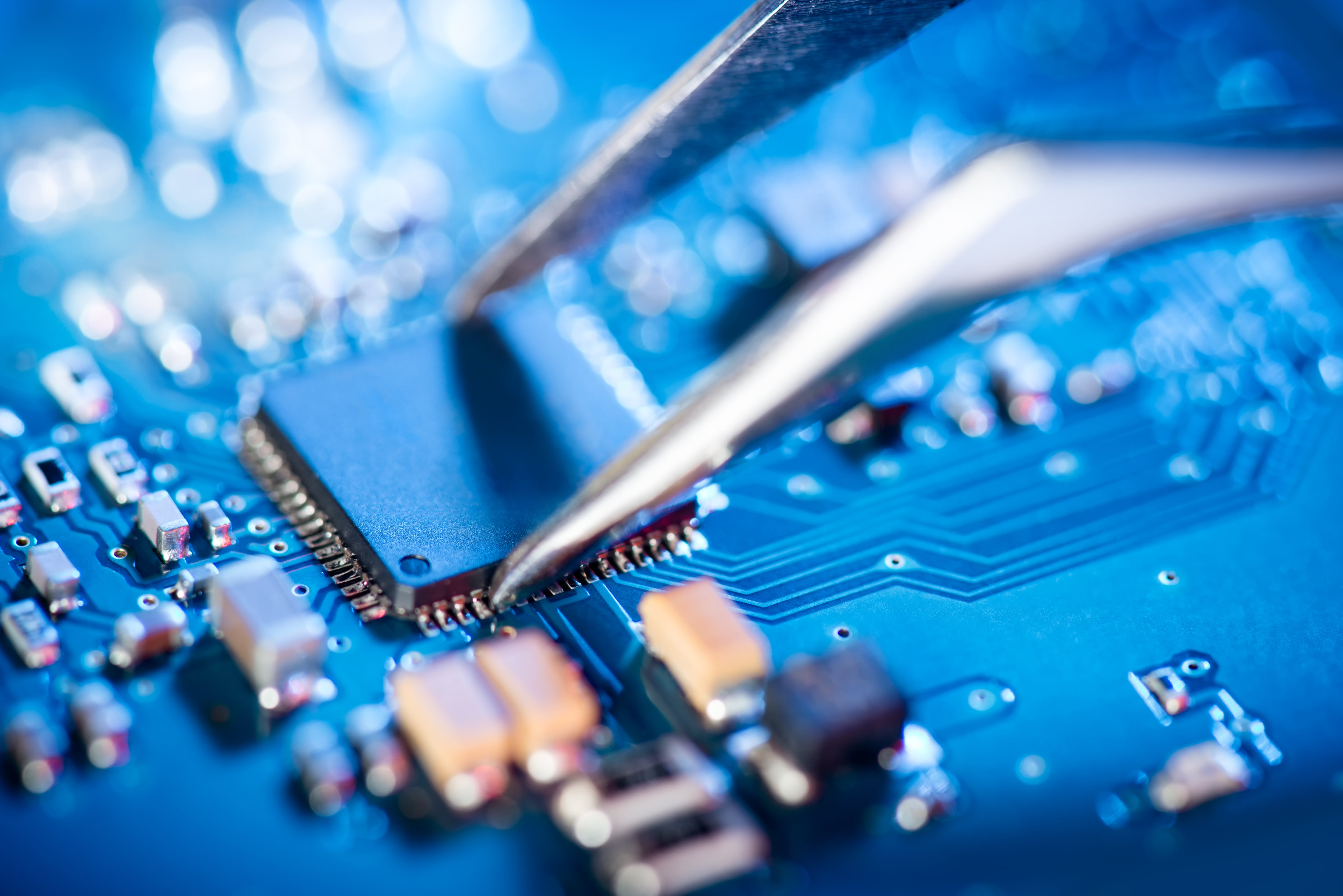

Semiconductors feed the defense, medical, industrial control and transportation sectors, to name just a few. America is confronted with a rising China that is committed to becoming the dominant technology power and increasingly poses an existential threat. We must quickly address critical supply chain security and resiliency issues. Both American soft and hard power are girded by our innovative technology and ability to apply it with agility to market demands and national security requirements.

Today, the U.S. commercial sector is America’s innovation engine, and private corporations are developing the intellectual property for our most advanced capabilities such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, quantum computing, space communications and sensing. And these dramatic leaps in technology are enabled by advancements in semiconductors. While semiconductors are the building blocks for the U.S. economy, so much of this industry has migrated overseas, and the resulting imbalance is a significant U.S. economic and national security threat.

The United States is at a precarious juncture where private and public sector missteps could erode our technological superiority, underscoring the urgency of addressing the semiconductor sector.

The People’s Republic of China understands the correlation between technology leadership, the economy and the military, which is why semiconductors are high on the PRC’s list of industries to develop for self-sufficiency and global leadership. Chips and semiconductor capabilities have received consistent and significant investment by the Chinese government. This internal emphasis has been matched by aggressive licit and illicit efforts to gain access to U.S. and other nations’ intellectual property.

Other foreign governments also have prioritized their semiconductor industries and heavily subsidized their chipmakers, contributing to the erosion of America’s semiconductor technology leadership position and the broader competitive environment. Moreover, the concentration of advanced semiconductor development and manufacturing carries not only considerable geopolitical risks but also resource constraints such as an interruption in water or power supplies. A one-hour power outage in a small area of Taiwan impacted 10% of the global DRAM — or dynamic random access memory — supply.

RELATED

Complicating U.S. policy options is the highly specialized, fragmented and time-consuming semiconductor production process. Furthermore, the supply chain for the raw materials needed to produce semiconductors is vast and complex, containing hidden chokepoints.

What is indisputable is that the U.S. needs a robust and resilient supply chain for semiconductors. U.S. government leaders should consider ways to promote greater robustness and resilience. They also should focus on the criticality of continuous innovation in microelectronics. We need our most essential IP to be developed, owned and protected here in the U.S. while perhaps leveraging the National Technology and Industrial Base partners.

Increasing manufacturing capacity does not itself contribute to U.S. technology leadership. This production capacity needs to be fed by capabilities derived from American developed, owned and protected IP. Widespread licensing from foreign companies creates not only an undesirable dependency, but over the long run it hinders technology leadership.

American leaps in innovation — e.g., the iPhone, the 787 Dreamliner, the reusable Falcon 9 rocket — were not created with IP licensed from abroad. The United States cannot be the world’s semiconductor leader or engine of advanced products if it merely builds domestic manufacturing capacity but relies on IP developed and owned overseas.

This importance of owning IP is why foreign companies base their IP — especially for advanced products — largely in their home countries, creating a virtuous cycle that sustains their competitive edge. That is also why foreign direct investment in the U.S. semiconductor industry makes a limited contribution in the long run to U.S. technology leadership. China, recognizing this, has developed an IP strategy meant to boost the number of patents held by Chinese companies in China.

What this means for the U.S. government is that it is not sufficient to subsidize chip manufacturing capacity; subsidies can be an accelerant supporting private sector investment but are not alone a solution. Subsidies as well as regulatory and tax policies should be designed to work together across the entire semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem — from process technology know-how through production and packaging.

We need to consider the requirements of U.S. semiconductor equipment manufacturers as well. Adding factory space, without the output of continuous innovation, risks that space being empty sometime in the future due to a lack of demand from a changing global market.

The competition with China will not be measured by leadership in square footage, but by intellectual leadership. We cannot expect to have the world’s leading economy without technological superiority — nor can we expect to have the world’s strongest military absent global economic leadership.

Both our allies and our adversaries have invested and continue to invest substantially in semiconductors. The U.S. is vulnerable, and this vulnerability is unacceptable. Upon funding of the CHIPS Act — otherwise known as the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act — the U.S. government should prioritize U.S. industry for focused financial support as well as consider the impact of proposed tax and regulatory measures on the U.S. semiconductor ecosystem.

Finally, the U.S. should establish clear lines of accountability and metrics to measure impact.

While the U.S. semiconductor industry’s global position has eroded, we have an opportunity to capitalize on the bipartisan consensus between Congress and the Biden administration. The challenge is to support this sector smartly and swiftly to ensure U.S. technological overmatch now and in the future.

Ellen Lord served as the first undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment. Prior to that, she was president and CEO of Textron Systems. She is currently a senior adviser of The Chertoff Group, where Mira Ricardel is a principal. Ricardel served as assistant to the president and deputy national security adviser. Prior to that, she was undersecretary of commerce for the Bureau of Industry and Security. The Chertoff Group has technology clients who may have an interest in this topic.